If Karl Marx were living today,

He’d be rolling around in his grave.

–Randy Newman

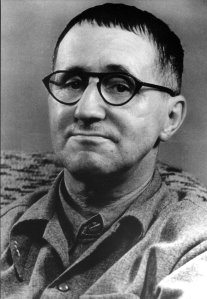

Bertolt Brecht’s play Mother Courage and Her Children had been around for sixteen years before it received its first production in the United States at the Actor’s Workshop in San Francisco in 1955. This was not because there had not been a capable English translation of the play before that time. New Directions had already published H. R. Hays’s English version in 1941. It is, rather, the politics of Mother Courage that undoubtedly delayed its premiere in the U. S. True, its less than ennobling portrait of war may not have been readily welcome to a nation that found itself on the verge of entering a global conflict that had already been raging across several continents for a number of years, but to imply that Mother Courage is merely an anti-war play seriously reduces the scope of its critique. And while the play’s merciless examination of the price of turning a profit suggests a critical framework grounded in Marxism—a political philosophy that may certainly have contributed to the reluctance of American theaters to produce it—its refusal of utopian solutions ultimately corrodes Marxist ideology, as well. Instead, what made its politics so troublesome was the attitude of critical skepticism that Mother Courage urges its audiences to adopt. The play compels spectators to question the necessity of the ways of the world that it portrays, a world that in the early 1940s too readily echoed the one roiling outside of the theater, just as it unfortunately does today. Basically, Mother Courage is radical because it provokes people to feel outrage at the choices foisted upon them by the economic conditions that have long dominated our world.

Anyone who has read Brecht’s sometimes startlingly nihilistic early plays such as Baal or In the Jungle of Cities knows that Mother Courage is not necessarily his most damning portrait of the world, but it is more disciplined than those earlier plays, making it more devastating. Moreover, Mother Courage more thoughtfully engages the critical possibilities of theater than his first plays, representing the fruition of theories about theater, art, and politics that Brecht had been developing since the 1920s. In fact, when it was first staged, it was probably his most fully realized version of what he called “epic theater” to date. Epic theater was the result of Brecht’s realization that in order to awaken in his audiences a critical attitude toward what he was showing them onstage, which they could hopefully take to the world outside of the theater, he could not rely on old dramatic forms. He understood that those forms themselves have meanings that shape whatever comes in contact with them, holding shut the curtains of audiences’ eyes by encouraging overly familiar habits of seeing. However, Brecht was also savvy enough to realize that a new form by itself was not radical, either. Theatrical form could only be radical insofar as it positioned the audience in an uneasy relationship with the drama. Epic theater was designed to position audiences so they would not get swept away by the events and emotions of the play, but would instead stand in judgment of it.

Brecht’s friend, the renowned critic Walter Benjamin, argued that epic theater was intended “to make the audience interested in the theatre as experts” so they could effectively consider and judge what they saw on stage. In a well-known essay about epic theater, Benjamin elaborated upon some of its defining characteristics, including: its reliance on familiar stories and historical events so audiences would be less interested in what is going to happen next than in what is happening at the moment it happens; its denial of fate by refusing to depict tragic heroes; the way it interrupts an overarching narrative in order to disrupt the audience’s desire to know what comes next as well as to “[arouse] astonishment rather than empathy” in them; its use of gestus, the “quotable gesture” that actors would use not only to interrupt the action of the play, but also to quote their own acting—making its materiality more consciously perceived—and to comment on the characters they are playing; and the fact that actors should not so much embody their characters as show themselves playing that character, striking a posture much as one might during a conversation, when showing somebody what another person said or did.

These aspects of epic theater are among the techniques Brecht employed to achieve what may be his most famous and misunderstood idea: the Alienation Effect. Since its inception, Brecht’s efforts to achieve the Alienation Effect seem to have inspired the cockeyed notion that Brecht wanted to banish all emotion from the theater, despite the fact that he once openly declared that Epic Theater “by no means renounces emotion, least of all the sense of justice, the urge to freedom, and righteous anger [. . .] but tries to arouse or to reinforce them.” Instead, Brecht wanted to alienate his audiences from what they were seeing, to defamiliarize what might have become so commonplace for them that it seemed part of the natural order of things, so that they could clearly see it for what it actually was and take a firm stand about what they thought of it. Unfortunately, many of the techniques Brecht devised for epic theater have been absorbed by the theater; they have become too familiar themselves. It’s hard to imagine audiences being shocked by a fragmented narrative, for example, or sputtering in outrage at exposed lighting equipment as they had been when Brecht first produced these plays.

One of the problems facing directors producing Mother Courage today, then, is whether to

“Mother Courage,” with, from left: Beatrice Manley, Stan Young, Malcolm Smith, Jinx Hone, and director Herbert Blau 1956.

alienate or not to alienate. As theater scholar Herbert Blau has said on a number of occasions, because of its familiarity and even because of all the misconceptions that are now inextricably bound to it, the Alienation Effect itself needs to be alienated. Regardless of what a director should choose to do, however, the intention of the Alienation Effect and epic theater must be kept in mind: audiences need to be filled with righteous anger at what they see. “The Song of the Great Capitulation” should not only arouse shame at what it may tell us about ourselves, it should drive us to fury, which requires that we be fully aware of what we’re seeing and hearing when Mother Courage sings her song. The play does its best to keep an audience off-balance so that they have to find their own legs, so to speak. The characters and events are rife with irony and contradictions, so that the attentive viewer cannot fall into easy habits of thought.

That is not to say that the play isn’t prey to readings that flatter rather than challenge one. No less than Tennessee Williams saw in Mother Courage’s final, pitiable act—in which she picks up her wagon to follow the war in spite of the fact that it is precisely this action that has cost her everything she holds most dear—a sign of the triumph of her indomitable will rather than the blind acceptance of her circumstances as simply the way things are, an almost stubborn refusal to learn from her suffering. There is nothing noble in Mother Courage’s last act. She is instead like the narrator of “The World Isn’t Fair,” the Randy Newman song I quoted at the beginning of my essay. What would make Karl roll around in his grave, the froggish narrator tells us, is that Marxism failed because it had to, because “the world it just isn’t fair, Karl/Never was and it never will be.” Though it’s probably not what the narrator had in mind, it’s just that kind of thinking that would have sent Karl Marx spinning prematurely in his grave. Why is the only choice available to us Marxism or unfairness? Why is it war or peace? What do you think? Where exactly, Mother Courage asks us, do you stand?

I learned a lot from this particular piece of yours. Thank you!

I’m glad to hear that, Kitty.